Kymatica focuses on human and universal consciousness and goes deeper into the metaphysical aspects of reality.

Εμφάνιση αναρτήσεων με ετικέτα Philosophy. Εμφάνιση όλων των αναρτήσεων

Εμφάνιση αναρτήσεων με ετικέτα Philosophy. Εμφάνιση όλων των αναρτήσεων

Τετάρτη 11 Ιουλίου 2012

Kymatica (Greek Subs)

Kymatica focuses on human and universal consciousness and goes deeper into the metaphysical aspects of reality.

Ετικέτες

Φιλοσοφια,

Helicon videos,

Philosophy

Σάββατο 21 Απριλίου 2012

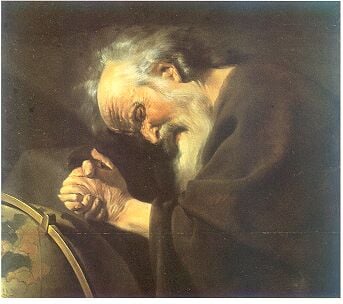

The Wisdom of Heraclitus

Wisdom 1: His Method

Here we will discuss the meaning of Heraclitus' fragments, and some of the difficulties and limitations of our interpretations of his philosophy. Heraclitus, the aristocratic Ephesian, was a deep and cryptic ancient Greek philosopher, and quite a unique thinker in the pre-Socratic tradition. We hope to examine his ideas within their historical context, but he breaks from his influences enough to make him well worthy of consideration (despite lacking almost all of his original writings) for his own ideas.

We rely on many excellent scholars to inform this discussion, such as Gregory Vlastos, W. K. C. Guthrie, G. S. Kirk, Charles Kahn, Martha Nussbaum, and others. (For those following along, citations will follow the Diels-Kranz numbering of fragments. Kahn translations were used for quotes, unless otherwise noted by name.) They don't all agree with each other, so we have to sometimes mention competing interpretations (especially for his flux doctrine).

It was common for pre-Socratic thinkers to speculate that order exists behind seemingly chaotic events. They are often called "natural philosophers" because they tried to explain everyday phenomena (with their eyes focused to the sky above and the earth below), but they were still generally different from the sort of theoretical and experimental scientists we have today.

Heraclitus was not fond of some of his fellow contemporaries, but through his biting criticisms of other thinkers and other scattered fragments, we detect four preferences that characterize his own methodology:

(1) As an isolated and independent thinker, his thought has a sense of originality. He claimed that he was not a synthesizer or gatherer of other philosopher's ideas like Pythagoras, whom Heraclitus criticizes as a leaner of "artful knavery" and polymathy (Fr. 129).

(2) He distrusted information gathered by hearsay and countered that we should get our information first hand through the senses (Fr. 55).

(3) He stressed the importance of searching within oneself, for by looking within one could find the same truths that preside over the cosmos as a whole. He has the conviction that we can best understand reality through reflection by the soul (Fr. 34) and the coherent comprehension of language (Fr. 107).

(4) He was not like other Presocratics who were concerned with geometry and pure natural philosophy, rather he was more concerned with oracular aphorisms or fragments that he believed conveyed deeper meaning (Fr. 45). His witty and paradoxical utterances form his own distinctive method in philosophy, borrowed perhaps from the Oracle at Delphi, who Heraclitus says does not instruct nor suppress the truth but gives a sign (Fr. 93).

His obscurity comes partly from his historical limitations such as the lack of certain logical distinctions, and his own methodological preferences. Heraclitus was at a point in history where he had little equipment to distinguish between a non-physical form and a material embodiment. Like the other Presocratic philosophers his ideas beg for such a distinction, which in part may explain his intuitive need for metaphorical language.

Heraclitus also prefers to think of reality as difficult to discover, or as he says: "the hidden attunement is better than the obvious one" (Fr. 54) and "nature is hidden" (Graham Fr. 123). And he posits a deep enough reality within us to make us skeptical of easily discovering knowledge (Fr. 45).

Wisdom 2: Reality of the Logos, Fire, and Elemental Transformation

Like the natural philosophers, Heraclitus posits a metaphysical reality (metaphysics here just means a discussion of an ultimate reality behind many deceptive appearances) that seeks to explain the way reality works behind the scenes despite the appearance of chaotic events around us.

Heraclitus calls his ultimate reality by many different names: the Logos (Fr. 1), fire (Fr. 64, 66), and God (Fr. 102). He does not in any of the existing fragments explicitly delineate a hierarchy between them. Exactly how each of these three forms of reality relates to each other is a mystery, but we do know that each of them has intelligible and directive qualities.

Kirk notes in his epilogue that Heraclitus most likely "used different terms according to differing moods and in different contexts -- e.g. fire in meteorological-cosmological contexts, god in synthetic ones where he is accepting traditional thought-patterns, Logos in logical-analytical ones". So we have to be careful not to strain our interpretations by trying to make Heraclitus' three types of oneness fit into a seamless, somewhat artificial framework.

A. Logos

He makes use of the word "Logos" differently from context to context, but in metaphysical contexts it translates as word or account, and some translators prefer "formula of things" or "language of reality" as a closer approximation of his meaning (Kirk, Grabowski). The precise definition of the Logos lurks far out of our reach, but we have a few hints as to his meaning.

He describes the Logos as either eternally true or eternally existent, and common to everyone. Since everything must work in accordance with it, it brings order to the world and allows us to justify our knowledge (Fr. 1, 2). It's arguable that he also elevates the activity of strife or flux itself as an ordering mechanism. For the most part, he speaks of the Logos in cases where he is concerned with knowledge and truth, yet he identifies fire as the most important "material" manifestation of the Logos.

We should point out that the distinction between material or nonphysical is not a distinction that Heraclitus or anyone else at this point in history made. But as interpreters often think of the Logos as a language of reality or the way in which things are arranged and ordered, they come close to making such a distinction.

We also find the same tension in the Pythagoreans, who made no distinction between form and matter, but spoke of numbers as the fundamental reality in such a way as to lead Aristotle to the view (perhaps mistakenly) that Plato's Forms, which are clearly specified as nonphysical, only differ in name from the Pythagoreans' numbers. In a similar way, it is as if Heraclitus' fragments are predisposed for a distinction between a formal rule (Logos) as the arrangement and basis of material things and the material things themselves (the elements).

B. Fire

Heraclitus describes fire in three parts as the "ever-living order", "same for all", and not made by any god or man (Fr. 30). He probably chose fire as one of his most important metaphors because it was the best of the recognized elements to fit into his scheme of change and unity: the fire flickers and appears stable as it consumes and gives off energy. Fire has the advantage, as Aristotle notes, that it moves on its own and needs no external cause to explain its motion.

But he is not like his predecessors, such as Anaximander, who saw one type of matter as the only reality. Instead he thought of his cosmic fire as the most important element and the manager of all things, which he states with the image of the divine fiery thunderbolt: "The thunderbolt pilots all things" (Fr. 64).

His scheme posited three elements, which are sea (probably water), earth, and prester (might be translated "lightning flash" or "whirlwind", but in this context it probably means something fiery such as fire), that are directed by the cosmic fire.

Heraclitus adds that all transformations between materials, and generally everything, are an equal exchange for fire: like "goods for gold and gold for goods" (Fr. 90). None of the three elements are in a completely steady state as they are said to be cycling in transformations into and out of one another always in an equal exchange.

For example, if part of sea transforms into earth, then an equal amount of earth would then have to transform back into sea (Fr. 31b). Kirk clarifies the elemental transformation cycle such that one-third of the sea changes to earth, one-third of the sea reverts to fire, and the other one-third remains sea (Fr. 31a).

A problem arises of how to reconcile the fragments in which Heraclitus considers everything a cosmic fire (see Fr. 30) when he also believes that there are three distinct elements (including fire in its elemental manifestation). How can one consider everything the cosmic fire if some parts of it are not fire?

To attempt to solve the problem (if it is solvable) we can follow Kirk and view the cosmic as "a fire like a huge bonfire, of which parts are temporarily dead, [and other] parts are not yet alight." In this view, the cosmic or pure fire steers and manages the processes of equal transformations of the elements without necessarily being them at every moment (Fr. 64, 66, 90).

By implication I think we might say the same about the Logos such that it provides an arrangement for the balance and flux in the cosmos without needing to do all the work, that is, control each part of the cosmos at every moment. We will see below that motion and internal tension may be said to create order on a smaller scale on their own (in that Logos would be redundant, and merely stand for the truth of the way reality works through the cosmic fire and its various manifestations).

Wisdom 3: Flux and Balance in all Things

We will now examine some of Heraclitus' most fascinating intuitions. Heraclitus presents us with three basic intuitions about the nature of reality: (1) everything is in a state of flux (even while sometimes stably persisting through time); (2) the harmony of opposite qualities create order and unity through strife; (3) possibly a third: time is important as another mechanism to the harmony and ultimate flux of things.

A. The Flux Doctrine: Stability Comes with Chaos

The most famous statement of the flux doctrine in Fr. 91b is the traditional, "One cannot step twice into the same river."

One may be tempted to interpret the fragment to mean that everything is in constant chaotic flux without order or balance. Some scholars, like Kirk, make such an interpretation and then dispute the authenticity of the quote. But other scholars, including Vlastos, defend it and argue that the flux doctrine is not fatal to the persistence of an object over time.

If the fragment is ambiguous and allows Kirk's interpretation, then it means that one cannot step into the same river and the river is never the same. However, this interpretation is equivalent to the view of Cratylus of Athens, a popular disciple of Heraclitus, who, as Aristotle notes, said one could not step into the same river once (Vlastos).

However, the fragment in question avoids this conclusion by saying that one cannot step into the same river twice. The fragment has two equal parts: one cannot step twice into the same waters and the river is the same. It most probably follows that the river has an identity and stays the same (in addition to its flux).

The second river-statement, Fr. 49a, is the paradoxical: "Into the same rivers we step and do not step, we are and we are not." The meaning is the same as in Fr. 91b since the fragment places both identity and change as two essential aspects of the river.

The authenticity of this fragment is controversial. Kahn dismisses Fr. 49a as a forgery since it looks to him as a refinery or combination of other fragments made by the source Heraclitus-Homericus. But Vlastos argues that what he calls the "yes-and-no" (step and do not step) form of writing in Fr. 49a is highly likely for Heraclitus for which there is no obvious precedent.

Since the river is meant as a metaphor, it seems intuitive that humans have identity and flux just like a river, so the meaning of "we are and are not" is similar to "being able and not able to step" into the same river. Despite Kahn's objection, the fragment at least seems consistent with Heraclitus' meaning.

We have a frequent problem interpreting Heraclitus' fragments, for one scholar may believe in the validity of a fragment and therefore differently construe the overall philosophy of Heraclitus accordingly. They must weigh the authenticity of sources, the possible intent of Heraclitus, coherence with other fragments, Heraclitus' probable use of language, and the accuracy of accounts from early commentators such as Aristotle and Plato. Guthrie, for example, makes an extended effort to validate Plato as a sound source in both reliability and emphasis, while Kirk believes that Aristotle is a better source for our knowledge of Heraclitus.

Kirk centers his interpretation on a conception of change in which balance and order (Logos) are essential to the river fragment and in which Heraclitus intends no underlying flux as the cause of the balance. He believes that the earliest source, Plato, paraphrases Heraclitus placing too much emphasis on change and disorder, which future commentators then mistook as Heraclitus' actual meaning. So he argues that Heraclitus did not imagine change on the minute or generalized level that Plato imagines.

Yet we can point to a fragment that might demonstrate that Plato captures the correct meaning of Heraclitus' flux doctrine (as Guthrie and Vlastos contend). During Heraclitus' life time there was a drink called a kykeon, sometimes translated as "potion", consisting of wine, barley, and grated cheese (Guthrie). The three parts of the potion-drink had to be constantly stirred or else they would break apart, so Heraclitus perhaps uses this image as a metaphor for what happens if motion were to cease: "Even the potion separates unless it is stirred" (Fr. 125). From this fragment we get the only explicit evidence that Heraclitus intends observed motion as essential to the identity of things (like rivers, people, etc.).

B. The Harmony of Strife and Opposite Qualities

The question also arises as to whether or not Heraclitus imagined change in places where common sense tells us that there is none. We look at a rock at one moment and only notice a motionless peaceful rock, but after a few years of weathering the rock may undergo significant changes.

The first hint that Heraclitus gives is stated in the following: "The ordering, the same for all, no god nor man has made, but it ever was and is and will be: fire everliving, kindled in measures and in measures going out" (Fr. 30).

If the fire in this fragment emphasizes fire in its symbolic meaning (that is, fire as an underlying reality and primary substance), then we cannot directly observe it kindling and going out in measure by perception. Several take this fragment to mean a cosmic fire, as Heraclitus was not a monist (Kirk & Raven). Hence, we can infer two characteristics evident at the imperceptible level according to Heraclitus: like a river, (a) the cosmic pure-fire is eternal and in harmony, (b) and it constantly undergoes change.

His bow fragments provide additional evidence that Heraclitus thought of an imperceptible flux functioning in things: "They do not comprehend how a thing agrees at variance with itself; it is an attunement turning back on itself, like that of the bow and the lyre" (Fr. 51).

Unlike water flowing in a river, the idle strung bow, we assume, is resting motionless. We must infer internal change by an investigation that when the taut string is cut the wooden bow will straighten out; hence, the inference is that the two parts were pulling against each other the whole time.

We agree that Heraclitus did not imagine minute material vibrations as modern scientists do, but instead he inferred a struggle or strife going on within seemingly peaceful objects. As we apply the flux doctrine to undetectable changes in a thing, we have essentially a "harmony of opposition" or "conflict doctrine". We have both the inner war occurring within the bow and fire (and as a metaphor for everything in general), and the outward change in rivers and potion-drinks.

We can summarize the relevant flux fragments as follows: (a) the river fragments demonstrate that observable identity and change are essential characteristics of things; (b) the potion-drink fragment gives us the notion that observable motion or flux causes order; (c) the cosmic fire and the bow fragments tell us that Heraclitus inferred flux not only as something that is observable but also that it occurs at the imperceptible level as well.

But he also used poetic words like "strife" and "war" to describe these instances of flux and internal tension. We can point to a couple fragments that demonstrate that Heraclitus thinks strife is the chief cause of order: "all things work in accordance with Strife" (Fr. 80) and "War is the father of all" (Fr. 53). We might summarize Heraclitus' flux argument by saying that the inward tugging and pulling of the bow is an instance of strife, but strife is the fundamental cause of its balance and identity.

Hence, strife seems to be inclusive of both the outward observed motion of a river and the internal tension of things like bows. Since motion and internal tension are both implied as causes of order in particular arrangements (as in the potion and bow fragments), they seem fundamental for order and unity to arise in Heraclitus' picture. Therefore, we can consider strife as the basic principle or mechanism for unity and balance in a thing.

Guthrie nicely phrases the consequence of this strife or flux doctrine: "There was law in the universe, but it was not a law of permanence, only a law of change, or, in something more like his own picturesque phraseology, the law of the jungle...."

Nietzsche colorfully says something similar as well: "The Things themselves in the permanency of which the limited intellect of man and animal believes, do not "exist" at all; they are as the fierce flashing and fiery sparkling of drawn swords, as the stars of Victory rising with a radiant resplendence in the battle of the opposite dualities."

Wisdom 4: Harmony of Oppositions Everywhere

Heraclitus knew nothing about particle bonds, but his harmony of opposites is similar to the way we currently think particles interact and are propelled by forces, except opposite qualities harmonize things together propelled by strife (that is, by motion and internal tension).

Heraclitus uses oppositions in several different contexts, but they allow him to advance many interesting critical parts of his thought. They show him questioning our hostility towards injustice, the arbitrary distinction between many of our words, and the existence of an all good God.

(1) In one group of fragments, Heraclitus notes how the existence of a term's opposite is necessary for us to account for the term's meaning and true nature; for example, without injustice, justice would presumably become meaningless (Fr. 102), and if one torpidly engorges oneself all the time, then satiety is meaningless since one does not have the contrast with displeasure and hunger (Fr. 111).

Some would like a world without any pain, agony, or war. But then would pleasure, happiness, and peace lose their meaningfulness?

(2) He also describes types of oppositions in which two terms, e.g. day and night, are only different in that they occur at different times and states of affairs, but are one in that they refer to the same world (Fr. 57). Another good example is his contention that waking and sleeping are the same and only different in that they succeed one another: a person goes to sleep and follows by waking up; therefore, he concludes that the sleeping is the "same" as the waking, that is they both refer to the same person (Fr. 88).

Perhaps he thinks that these arbitrary labels cloak an underlying unity in the world. A unity that is best characterized with our senses and self-reflection, rather than our blind acceptance of arbitrary categories, labels, and ideal distinctions. As with the first type of duality, he mistrusts popular attempts to divide the world, say, into good and bad with mere blunt words, which miss the unity and dependence they have on each other (specifically on their opposites).

(3) He observes other types of opposition that unite together in oneness, not by succession or time, but by being united in a metaphysical substance such as God. For example, he says that God is both "day and night, winter and summer, war and peace, satiety and hunger," and later humans label or baptize them different names to distinguish them from one another. But they are fundamentally united together in that they, war and peace, are both equally a part of God (Fr. 67).

In this regard, one can note that Heraclitus disagrees with those who would only assign good intentions to the divine and godly realm, for he does not think that peace alone could exist or be meaningful without its opposite (so both are necessary and divine).

Another similar example is where two perceivers interact with the same thing but attribute it opposite qualities. For example, the salty sea is both pure and foul because it is healthy and good for fish, but for men it is "undrinkable and deadly" (Fr. 61). This implies that a sea has the ability to produce both opposite effects to those who make use of it, and it can have positive and negative traits depending on the perspective of the thing that interacts with the sea. Humans might think of sea water as negative since it can have a bad effect on them, but animals that need the sea for their survival experience the sea in positive terms.

This list of oppositions is not complete, but it is sufficient for a picture of some of his interesting uses of his harmony of oppositions.

Wisdom 5: Time and Degrees of Identity

The harmony of oppositions also suggest the importance of Heraclitus' third major intuition of reality concerning the nature of time. We can interpret the passage of ever new waters in a river also as the passing of time. And the amount of change that one interprets, whether a constant flux at the imperceptible level or a more conservative conception of change, means little to the passage of time. In the end most everything dies in a transformation into other elements.

An essential unity captured by the passage of time consists in temporal oppositions, such as "day and night are one" (Fr. 57). Heraclitus did not view this type of opposition as a conflict between things, which he implies in his explanation of their oneness in the following: "For these things when they have changed are those, and those when they have changed are these" (Fr. 88).

He says day and night are the "same" because they alter in attributes or succeed one another, not because they are in conflict or have an exact identity with each other. We could say that these are like a binding bridge to tie the kosmos together, connecting it together by time, degree of change, and necessity.

However, taking a long term view that time ultimately destroys all things (in a cycle of elemental transformations), we can say that the most essential aspect of being or reality is activity. Although in outward balance and harmony, everything in existence necessarily changes over time and in the end transforms into something else, so we commonly find ourselves talking about a "becoming" rather than a "being".

Why speak of something's true nature if time and necessity will eventually wash it away? If we take the question to an extreme, we can only talk about an essential nature or identity of something when we discuss the Logos or cosmic fire itself, that is, if we want certain unbending truths.

But depending on how much flux we attribute to the river example we will find that the river stays constant enough for us to place our foot into it, and, we can imagine, it will not be so different the next time.

Difference is often seen as either the identity of the river is lost and becomes completely "different" or it is not, but here we refer to degrees of difference. The problem of degrees weighs heavily as we try to decipher Heraclitus' intentions in his riddling fragments.

Does hot turn into cold instantly or slowly? Is hot a degree of coldness and cold a degree of warmness? That Heraclitus thought of the problem in degrees is difficult to tell since his poetic method is phrased in either-or language.

Judging from his some of his fragments on opposites, we can suggest that Heraclitus could think in degrees (the way in-between) even though he wrote mostly in either-or oppositions; for example, he notes that the way up and the way down is one and the same because the way between them is the same (Fr. 60).

Wisdom 6: The Rational Psyche

As we now turn to man as a microcosm, we find that few scholars disagree on the view that the cosmic fire is analogous to the psyche. In a fragment on transformations of elements Heraclitus uses the word soul where we would naturally expect him to write fire (Fr. 36).

By placing soul on the same level as the cosmic fire, he superimposes chunks of his philosophy to the sphere of humans. He namely thinks that a person's psyche becomes like the world-ordering fire.

Nussbaum argues that Heraclitus is the first known philosopher to describe the psyche as a central unity that accounts for the use and evaluation of language, while also representing the life-activity of the person.

Heraclitus criticizes Homer's depiction of humans mainly learning information through sudden intuitions. He thinks this would leave the soul thoughtless and subjective and, more importantly, shut off from the common Logos (preventing us from regularly attaining knowledge).

We would be able to say that animals have similar mental abilities as humans if we just include body parts (eye, ear, etc.) as significant to knowledge. But Heraclitus emphasizes the importance of language in human reasoning, which is peculiar to humans.

Heraclitus describes the soul's use of language and reason as its rational agency (and also the part of the soul that is similar to the cosmic fire). Since the soul uses the same type of rational language of the Logos, it is able to seek knowledge of the Logos (or the formula of things).

Wisdom 7: Anonymous Soul

Any interpretation of his remarks on immortality need to refer to his cosmological fragments. Heraclitus may or may not advocate the immortality of the soul. If he does then the immortality we receive is not like anything that one typically desires of an afterlife. That is, if we assume that most people want to preserve their identity, including their life memories and experiences in the hereafter.

But in Heraclitus' cosmology we have no way of distinguishing one soul from another. We discussed that the cosmic fire is one reality that transforms between many different elements. After the soul dies and transforms, it is lost to the many parts of the cosmic fire. And some elements in it are not very soul-like, such as water and earth.

We can say that the general material and rational language of the soul survive (the "language of nature" and any part of us that became knowledgeable about how reality might work). The reality of the Logos, which the soul may come into contact with, persists past the death of the soul. But we have no way of saying that our individual traits or miscellaneous memories survive.

It's an interesting question whether Heraclitus would go as far as Spinoza, and suggest that we share a sense of immortality when we understand eternal laws of nature. In any case, the immortality would be as interesting as grasping the flux doctrine intellectually. It's just not something to write home about; it's something to take a philosophy seminar on! You would lose your lifetime achievements, personal identity, and unique experiences.

Nussbaum additionally argues (based on textual and historical analysis) that in fragments where Heraclitus mentions the soul living after death, he might be referring to the fame of the individual in the minds of future generations.

Therefore, on this interpretation we can account for the reason why Heraclitus praises fame: the courageous soldier in battle gets honor from the gods and men (Fr. 24) and greater deaths get better destinies (Fr. 25). We can also understand why the gods honor men, for the gods are immortal and cannot risk their lives, so they cannot attain virtue through battle (Nussbaum).

Other interpreters take the opposite view and believe that the only way to account for Heraclitus' use of soul is to provide for some sort of immortality, but such an interpretation is incoherent with the necessity of change, strife, and elemental transformations that we adopted earlier. The soul must transform to some other non-soul-like substance, such as water or earth.

Wisdom 8: Strife is Good, from a Certain Point of View!

Heraclitus rebels against Anaximander's moralizing account of nature, which claims that materials pay a price for their transgressions against the peaceful order of things. Heraclitus instead believes that strife is just, good, and desirable (Fr. 80), for balance and order can not exist without conflict. So we cannot condemn the necessity of strife.

Aristotle also remarks in Eudemian Ethics (1235a25) that Heraclitus chided Homer for his poetic wish to end conflict, since there would be "no harmony without both high and low notes" (Fr. A22).

This may be startling and ghastly for some to conceive: war is right and good and unavoidable. Most people are in the nature of advocating peace and harmony, but they, says Heraclitus, should look within peace.

We should emphasize that Heraclitus would possibly say that a rock is at "war" when it is sitting motionless and idle, apparently doing nothing. So, here, we find "the Riddler" devising his own personal vocabulary and outlook on life that we might expect from such an original, isolated and independent thinker, and at the same time as a result of his philosophical views. He prefers his own reflective vision of Logos over the language of the commoners.

Wisdom 9: Moral Exceptionalism

Another key aspect of Heraclitus' ethical views is that he advocates a noble moral outlook. He would choose the best person from the crowd instead of several average types (Fr. 49), and this implies that he makes a qualitative distinction between people.

In other fragments, e.g. where he envisions the punishment of whole cities for the sake of a defiled better man among them (Fr. 121), we also find that he does not endorse an equalizing ethical code that grants all people the same moral status.

But at the same time he wants us to live in accordance with the law of one and to defend the walls of our cities, so he does not believe in leaving one's society in moral chaos; therefore, he echoes the entire ancient Greek culture that tended to think of balance and measure as best.

Wisdom 10: Temperance

Heraclitus symbolizes the right road to attaining truth as the "dry soul" (Fr. 118) and the wrong way as the "wet soul" (Fr. 117). He thinks that a dry soul should live a temperate life (Fr. 112) and avoid the bestial pleasures of the body (Fr. 4).

Nussbaum argues that his reasons for rejecting the life of a wet soul: "the shamefulness of the wet state of psyche consists, apparently, in a loss of self-direction, self-awareness, self-control."

Heraclitus does not, however, distinguish between the amount of "wetness" we are allowed or how much "dryness" we should desire, so we have no way to tell if Heraclitus advocates a completely "dry" life or a moderate one.

Final Remarks

Heraclitus might have counseled that while our soul is still active in us, we can work on achieving a greater amount of self-knowledge and knowledge of the Logos, but it is not easy to grasp and some parts of it may always remain out of our reach (and most men fail to grasp it altogether). Things tend to keep their secrets.

Possibly he believes that we can come closer to an understanding of it with the proper use of language and reason (by solving its riddles, we could say). And we have a better chance if we use the other methods outlined in the introduction (self knowledge, sense perception, etc.).

His aphoristic method compacts a lot of meaning into each of his fragments, and they can be unpacked in many different ways. Heraclitus' philosophy is like Zeus' thunderbolt that strikes to the root of its spectators from a distance, and strikes deep enough to lend to multiple interpretations (none of which are perfectly resolved by any two scholars).

But we can hope that by careful analysis of his time, language, history, and influences, we can reason along with his intended meanings and transmit his wisdom to the future. Deep thinkers tend to get misunderstood and dismissed with contemptuous rhetoric, but rare thinkers are a cherished commodity in the marketplace of ideas. Heraclitus will be difficult to ignore.

He would probably council us to exert our own rationality in considering his wisdom, and put aside the urge to dismiss his meditations with contemptuous political correctness, mere rumors or cultural habits, or academic pseudo-knowledge that all too often lacks critical reflection.

Works Cited (Main Sources)

Guthrie, W. K. C. "Heraclitus." History of Greek Philosophy. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1962. 403-492.

Kahn, Charles H. The Art and Thought of Heraclitus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

Kirk, G. S. & Raven, J. E. The Presocratic Philosophers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1957.

Kirk, G. S. Heraclitus: The Cosmic Fragments. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1962.

Nussbaum, Martha C. "Psyche in Heraclitus." Phronesis 17 (1972): 1-16, 153-170.

Vlastos, Gregory. "On Heraclitus." The American Journal of Philosophy 76 (1955): 337-368.

Additional Works Cited (One Citation or Less)

Benardete, S. "On Heraclitus." The Review of Metaphysics 53 (2000): 613-633.

Grabowski, Frank. "Issues Surrounding Logos in Heraclitus, Fragment B56." Michigan Academician 32 (2000): 267-282.

Graham, Daniel W. "Does Nature Love to Hide?" Classical Philology 98 (2003): 175-80.

Haxton, Brooks. Fragments: The Collected Wisdom of Heraclitus. New York: Viking, 2001.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. Early Greek Philosophy: and Other Essays. Trans. Mugge, Maximillian A. Edinburgh: The Darien Press, 1911.

Ετικέτες

Articles in English,

Cosmos,

Philosophy

HERACLITUS OF EPHESUS

HERACLITUS OF EPHESUS

The G.W.T. Patrick translation*

1

Οὐκ ἐμεῦ ἀλλὰ τοῦ λόγου ἀκούσαντας ὁμολογέειν σοφόν ἐστι, ἓν πάντα εἶναι.

It is wise for those who hear, not me, but the universal Reason, to confess that all things are one.

SOURCES--Hippolytus, Ref. haer. ix. 9. Context:--Heraclitus says that all things are one, divided undivided, created uncreated, mortal immortal, reason eternity, father son, God justice. "It is wise for those who hear, not me, but the universal Reason, to confess that all things are one." And since all do not comprehend this or acknowledge it, he reproves them somewhat as follows: "They do not understand how that which separates unites with itself; it is a harmony of oppositions like that of the bow and of the lyre" (=frag. 45).

Compare Philo, Leg. alleg. iii. 3, p. 88. Context, see frag: 24.

2

Τοῦ δὲ λόγου τοῦδ' ἐόντος αἰεὶ ἀξύνετοι γίγνονται ἄνθρωποι καὶ πρόσθεν ἢ ἀκοῦσαι καὶ ἀκούσαντες τὸ πρῶτον. γινομένων γὰρ πάντων κατὰ τὸν λόγον τόνδε ἀπείροισι ἐοίκασι πειρώμενοι καὶ ἐπέων καὶ ἔργων τοιουτέων ὁκοίων ἐγὼ διηγεῦμαι, διαιρέων ἕκαστον κατὰ φύσιν καὶ φράζων ὅκως ἔχει. τοὺς δὲ ἄλλους ἀνθρώπους λανθάνει ὁκόσα ἐγερθέντες ποιέουσι, ὅκωσπερ ὁκόσα εὕδοντες ἐπιλανθάνονται.

To this universal Reason which I unfold, although it always exists, men make themselves insensible, both before they have heard it and when they have heard it for the first time. For notwithstanding that all things happen according to this Reason, men act as though they had never had any experience in regard to it when they attempt such words and works as I am now relating, describing each thing according to its nature and explaining how it is ordered. And some men are as ignorant of what they do when awake as they are forgetful of what they do when asleep.

SOURCES--Hippolytus, Ref. haer. ix. 9. Context:--And that Reason always exists, being all and permeating all, he (Heraclitus) says in this manner: "To this universal," etc.

Aristotle, Rhet. iii. 5, p. 1407,b. 14. Context:--For it is very hard to punctuate Heraclitus' writings on account of its not being clear whether the words refer to those which precede or to those which follow. For instance, in the beginning of his work, where he says, "To Reason existing always men make themselves insensible." For here it is ambiguous to what "always" refers.

Sextus Empir. adv. Math. vii. 132.--Clement of Alex. Stromata, v. 14, p. 716.--Amelius from Euseb. Praep. Evang. xi. 19, p. 540.-- Compare Philo, Quis. rer. div. haer. 43, p. 505.--Compare Ioannes Sicel. in Walz. Rhett. Gr. vi. p. 95.

3

Ἀξύνετοι ἀκούσαντες κωφοῖσι ἐοίκασι· φάτις αὐτοῖσι μαρτυρέει παρεόντας ἀπεῖναι.

Those who hear and do not understand are like the deaf. Of them the proverb says: "Present, they are absent."

SOURCES--Clement of Alex. Strom. v. 14, p. 718. Context:--And if you wish to trace out that saying, "He that hath ears to hear, let him hear," you will find it expressed by the Ephesian in this manner," Those who hear," etc.

Theodoretus, Therap. i. p. 13, 49.

4

Κακοὶ μάρτυρες ἀνθρώποισι ὀφθαλμοὶ καὶ ὦτα, βαρβάρους ψυχὰς ἐχόντων.

Eyes and ears are bad witnesses to men having rude souls.

SOURCES--Sextus Emp. adv. Math. vii. 126. Context:--He (Heraclitus) casts discredit upon sense perception in the saying, "Eyes and ears are bad witnesses to men having rude souls." Which is equivalent to saying that it is the part of rude souls to trust to the irrational senses.

Stobaeus Floril. iv. 56.

Compare Diogenes Laert. ix. 7.

5

Οὐ φρονέουσι τοιαῦτα πολλοὶ ὁκόσοισι ἐγκυρέουσι οὐδὲ μαθόντες γινώσκουσι, ἑωυτοῖσι δὲ δοκέουσι.

The majority of people have no understanding of the things with which they daily meet, nor, when instructed, do they have any right knowledge of them, although to themselves they seem to have.

SOURCES--Clement of Alex. Strom. ii. 2, p. 432.

M. Antoninus iv. 46. Context:--Be ever mindful of the Heraclitic saying that the death of earth is to become water, and the death of water is to become air, and of air, fire (see frag. 25). And remember also him who is forgetful whither the way leads (comp. frag. 73); and that men quarrel with that with which they are in most continual association (=frag. 93), namely, the Reason which governs all. And those things with which they meet daily seem to them strange; and that we ought not to act and speak as though we were asleep (= frag. 94), for even then we seem to act and speak.

6

Ἀκοῦσαι οὐκ ἐπιστάμενοι οὐδ' εἰπεῖν.

They understand neither how to hear nor how to speak.

SOURCES--Clement of Alex. Strom. ii. 5, p. 442. Context:--Heraclitus, scolding some as unbelievers, says: "They understand neither how to hear nor to speak," prompted, I suppose, by Solomon, "If thou lovest to hear, thou shalt understand; and if thou inclinest thine ear, thou shalt be wise."

7

Ἐὰν μὴ ἔλπηαι, ἀνέλπιστον οὐκ ἐξευρήσει, ἀνεξερεύνητον ἐὸν καὶ ἄπορον.

If you do not hope, you will not win that which is not hoped for, since it is unattainable and inaccessible.

SOURCES--Clement of Alex. Strom. ii. 4, p. 437. Context:--Therefore, that which was spoken by the prophet is shown to be wholly true, "Unless ye believe, neither shall ye understand." Paraphrasing this saying, Heraclitus of Ephesus said, "If you do not hope," etc.

Theodoretus, Therap. i. p. 15, 51.

8

Χρυσὸν οἱ διζήμενοι γῆν πολλὴν ὀρύσσουσι καὶ εὑρίσκουσι ὀλίγον.

Gold-seekers dig over much earth and find little gold.

SOURCES--Clement of Alex. Strom. iv. 2, p. 565.

Theodoretus, Therap. i. p. 15, 52.

9

Ἀγχιβασίην.

Debate.

SOURCES--Suidas, under word amphisbatein, enioi to amphisbêtein Iônes de kai angchibasiên Hêraclitus.

10

Φύσις κρύπτεσθαι φιλεῖ

Nature loves to conceal herself.

SOURCES--Themistius, Or. v. p. 69 (=xii. p. 159). Context:--Nature according to Heraclitus, loves to conceal herself; and before nature the creator of nature, whom therefore we especially worship and adore because the knowledge of him is difficult.

Philo, Qu. in Gen. iv. 1, p. 237, Aucher.: Arbor est secundum Heraclitum natura nostra, quae se obducere atque abscondere amat.

Compare idem de Profug. 32, p. 573; de Somn. i. 2, p. 621; de Spec. legg. 8, p. 344.

11

Ὁ ἄναξ οὗ τὸ μαντεῖόν ἐστι τὸ ἐν Δελφοῖς, οὔτε λέγει οὔτε κρύπτει, ἀλλὰ σημαίνει.

The God whose oracle is at Delphi neither speaks plainly nor conceals, but indicates by signs.

SOURCES--Plutarch, de Pyth. orac. 21, p. 404. Context:--And I think you know the saying of Heraclitus that "The God," etc.

Iamblichus, de Myst. iii. 15.

Idem from Stobaeus Floril. lxxxi. 17.

Anon. from Stobaeus Floril. v. 72.

Compare Lucianus, Vit. auct. 14.

12

Σίβυλλα δὲ μαινομένῳ στόματι ἀγέλαστα καὶ ἀκαλλώπιστα καὶ ἀμύριστα φθεγγομένη χιλίων ἐτέων ἐξικνέεται τῇ φωνῇ διὰ τὸν θεόν.

But the Sibyl with raging mouth uttering things solemn, rude and unadorned, reaches with her voice over a thousand years, because of the God.

SOURCES--Plutarch, de Pyth. orac. 6, p. 397. Context:--But the Sibyl, with raging mouth, according to Heraclitus, uttering things solemn, rude and unadorned, reaches with her voice over a thousand years, because of the God. And Pindar says that Cadmus heard from the God a kind of music neither pleasant nor soft nor melodious. For great holiness permits not the allurements of pleasures.

Clement of Alex. Strom. i. 15, p. 358.

Iamblichus, de Myst. iii. 8.

See also pseudo-Heraclitus, Epist. viii.

13

Ὅσων ὄψις ἀκοὴ μάθησις, ταῦτα ἐγὼ προτιμέω.

Whatever concerns seeing, hearing, and learning, I particularly honor.

SOURCES--Hippolytus, Ref. haer. ix. 9, 10. Context:--And that the hidden, the unseen and unknown to men is [better], he (Heraclitus) says in these words, "A hidden harmony is better than a visible " (= frag. 47). He thus praises and admires the unknown and unseen more than the known. And that that which is discoverable and visible to men is [better], he says in these words, "Whatever concerns seeing, hearing, and learning, I particularly honor," that is, the visible above the invisible. From such expressions it is easy to understand him. In the knowledge of the visible, he says, men allow themselves to be deceived as Homer was, who yet was wiser than all the Greeks; for some boys killing lice deceived him saying, "What we see and catch we leave behind; what we neither see nor catch we take with us " (frag. 1, Schuster). Thus Heraclitus honors in equal degree the seen and the unseen, as if the seen and unseen were confessedly one. For what does he say? "A hidden harmony is better than a visible," and, "whatever concerns seeing, hearing, and learning, I particularly honor," having before particularly honored the invisible."

14

Polybius iv. 40: τοῦτο γὰρ ἴδιόν ἐστι τῶν νῦν καιρῶν, ἐν οἷς πάντων πλωτῶν καὶ πορευτῶν γεγονότων οὐκ ἂν ἔτι πρέπον εἴη ποιηταῖς καὶ μυθογράφοις χρῆσθαι μάρτυσι περὶ τῶν αγνοουμένων, ὅπερ οἱ πρὸ ἡμῶν περὶ τῶν πλείστων, ἀπίστους ἀμφισβητουμένων παρεχόμενοι βεβαιωτὰς κατὰ τὸν Ἡράκλειτον.

Polybius iv. 40. Especially at the present time, when all places are accessible either by land or by water, we should not accept poets and mythologists as witnesses of things that are unknown, since for the most part they furnish us with unreliable testimony about disputed things, according to Heraclitus.

15

Ὀφθαλμοὶ τῶν ὤτων ἀκριβέστεροι μάρτυρες.

The eyes are more exact witnesses than the ears.

SOURCES--Polybius xii. 27. Context:--There are two organs given to us by nature, sight and hearing, sight being considerably the more truthful, according to Heraclitus, "For the eyes are more exact witnesses than the ears."

Compare Herodotus i. 8.

16

Πολυμαθίη νόον ἔχειν οὐ διδάσκει· Ἡσίοδον γὰρ ἂν ἐδίδαξε καὶ Πυθαγόρην αὖτις τε Ξενοφάνεα καὶ Ἑκαταῖον.

Much learning does not teach one to have understanding, else it would have taught Hesiod and Pythagoras, and again Xenophanes and Hecataeus.

SOURCES--Diogenes Laert. ix. 1. Context:--He (Heraclitus) was proud and disdainful above all men, as indeed is clear from his work, in which he says, "Much learning does not teach," etc.

Aulus Gellius, N. A. praef. 12.

Clement of Alex. Strom. i. 19, p. 373.

Athenaeus xiii. p. 610 B.

Iulianus, Or. vi. p. 187 D.

Proclus in Tim. 31.F.

Serenus in Excerpt. Flor. Ioann. Damasc. ii. 116, p. 205, Meinek.

Compare pseudo-Democritus, fr. mor. 140 Mullach.

17

Πυθαγόρης Μνησάρχου ἱστορίην ἤσκησε ἀνθρώπων μάλιστα πάντων. καὶ ἐκλεξάμενος ταύτας τὰς συγγραφὰς ἐποίησε ἑωυτοῦ σοφίην, πολυμαθίην, κακοτεχνίην.

Pythagoras, son of Mnesarchus, practised investigation most of all men, and having chosen out these treatises, he made a wisdom of his own--much learning and bad art.

SOURCES--Diogenes Laert. viii. 6. Context:--Some say, foolishly, that Pythagoras did not leave behind a single writing. But Heraclitus, the physicist, in his croaking way says, "Pythagoras, son of Mnesarchus," etc.

Compare Clement of Alex. Strom. i. 21, p. 396.

18

Ὁκόσων λόγους ἤκουσα οὐδεὶς ἀφικνέεται ἐς τοῦτο, ὥστε γινώσκειν ὅτι σοφόν ἐστι πάντων κεχωρισμένον.

Of all whose words I have heard, no one attains to this, to know that wisdom is apart from all.

SOURCES--Stobaeus Floril. iii. 81.

19

Ἓν τὸ σοφόν, ἐπίστασθαι γνώμην ᾗ κυβερνᾶται πάντα διὰ πάντων.

There is one wisdom, to understand the intelligent will by which all things are governed through all.

SOURCES--Diogenes Laert. ix. 1. Context:--See frag. 16.

Plutarch, de Iside 77, p. 382. Context:--Nature, who lives and sees, and has in herself the beginning of motion and a knowledge of the suitable and the foreign, in some way draws an emanation and a share from the intelligence by which the universe is governed, according to Heraclitus.

Compare Cleanthes H. in Iov. 36.

Compare pseudo-Linus, 13 Mullach.

20

Κόσμον <τόνδε> τὸν αὐτὸν ἁπάντων οὔτε τις θεῶν οὔτε ἀνθρώπων ἐποίησε, ἀλλ' ἦν αἰεὶ καὶ ἔστι καὶ ἔσται πῦρ ἀείζωον, ἁπτόμενον μέτρα καὶ ἀποσβεννύμενον μέτρα.

This world, the same for all, neither any of the gods nor any man has made, but it always was, and is, and shall be, an ever living fire, kindled in due measure, and in due measure extinguished.

SOURCES--Clement of Alex. Strom. v. 14, p. 711. Context:--Heraclitus of Ephesus is very plainly of this opinion, since he recognizes that there is an everlasting world on the one hand and on the other a perishable, that is, in its arrangement, knowing that in a certain manner the one is not different from the other. But that he knew an everlasting world eternally of a certain kind in its whole essence, he makes plain, saying in this manner, "This world the same for all," etc.

Plutarch, de Anim. procreat. 5, p. 1014. Context:--This world, says Heraclitus, neither any god nor man has made; as if fearing that having denied a divine creation, we should suppose the creator of the world to have been some man.

Simplicius in Aristot. de cael. p. 132, Karst.

Olympiodorus in Plat. Phaed. p. 201, Finckh.

Compare Cleanthes H., Iov. 9.

Nicander, Alexiph. 174.

Epictetus from Stob. Floril. cviii. 60.

M. Antoninus vii. 9.

Just. Mart. Apol. p. 93 C.

Heraclitus, Alleg. Hom. 26.

21

Πυρὸς τροπαὶ πρῶτον θάλασσα· θαλάσσης δὲ τὸ μὲν ἥμισυ γῆ, τὸ δὲ ἥμισυ πρηστήρ.

The transmutations of fire are, first, the sea; and of the sea, half is earth, and half the lightning flash.

SOURCES--Clement of Alex. Strom. v. 14, p. 712. Context:--And that he (Heraclitus) taught that it was created and perishable is shown by the following, "The transmutations," etc.

Compare Hippolytus, Ref. haer. vi. 17.

22

Πυρὸς ἀνταμείβεται πάντα καὶ πῦρ ἁπάντων, ὥσπερ χρυσοῦ χρήματα καὶ χρημάτων χρυσός.

All things are exchanged for fire and fire for all things, just as wares for gold and gold for wares.

SOURCES--Plutarch, de EI. 8, p. 388. Context:--For how that (scil. first cause) forming the world from itself, again perfects itself from the world, Heraclitus declares as follows, "All things are exchanged for fire and fire for all things," etc.

Compare Philo, Leg. alleg. iii. 3, p. 89. Context, see frag. 24.

Idem, de Incorr. mundi 21, p. 508.--Lucianus, Vit. auct. 14.

Diogenes Laert. ix. 8.

Heraclitus, Alleg. Hom. 43.

Plotinus, Enn. iv. 8, p. 468.--Iamblichus from Stob. Ecl. i. 41.

Eusebius, Praep. Evang. xiv. 3, p. 720.--Simplicius on Aristot. Phys. 6, a.

23

Θάλασσα διαχέεται καὶ μετρέεται ἐς τὸν αὐτὸν λόγον ὁκοῖος πρόσθεν ἦν ἢ γενέσθαι †γῆ†.

The sea is poured out and measured to the same proportion as existed before it became earth.

SOURCES--Clement of Alex. Strom. v. 14, p. 712 (=Eusebius, P. E. xiii. 13, p. 676). Context:--For he (Heraclitus) says that fire is changed by the divine Reason which rules the universe, through air into moisture, which is as it were the seed of cosmic arrangement, and which he calls sea; and from this again arise the earth and the heavens and all they contain. And how again they are restored and ignited, he shows plainly as follows, "The sea is poured out," etc.

24

Χρησμοσύνη . . . κόρος.

Craving and Satiety.

SOURCES--Hippolytus, Ref. haer. ix. 30. Context:--And he (Heraclitus) says also that this fire is intelligent and is the cause of the government of all things. And he calls it craving and satiety. And craving is, according to him, arrangement (diakosmêsis), and satiety is conflagration (ekpyrôsis). For, he says, " Fire coming upon all things will separate and seize them " (= frag. 26).

Philo, Leg. alleg. iii. 3, p. 88. Context:--And the other (scil. ho gonorruês), supposing that all things are from the world and are changed back into the world, and thinking that nothing was made by God, being a champion of the Heraclitic doctrine, introduces craving and satiety and that all things are one and happen by change.

Philo, de Victim. 6, p. 242.

Plutarch, de EI. 9, p. 389.

25

Ζῇ πῦρ τὸν γῆς θάνατον, καὶ ἀὴρ ζῇ τὸν πυρὸς θάνατον· ὕδωρ ζῇ τὸν ἀέρος θάνατον, γῆ τὸν ὕδατος.

Fire lives in the death of earth, air lives in the death of fire, water lives in the death of air, and earth in the death of water.

SOURCES--Maximus Tyr. xli. 4, p. 489. Context:--You see the change of bodies and the alternation of origin, the way up and down, according to Heraclitus. And again he says, "Living in their death and dying in their life (see frag. 67). Fire lives in the death of earth" etc.

M. Antoninus iv. 46. Context, see frag. 5.

Plutarch, de EI. 18, p. 392.

Idem, de Prim. frig. 10, p. 949. Comp. pseudo-Linus 21, Mull.

26

Πάντα τὸ πῦρ ἐπελθὸν κρινέει καὶ καταλήψεται.

Fire coming upon all things, will sift and seize them.

SOURCES-- XXVI.--Hippolytus, Ref. haer. ix. 10. Context, see frag. 24.

Compare Aetna v. 536: quod si quis lapidis miratur fusile robur, cogitet obscuri verissima dicta libelli, Heraclite, tui, nihil insuperabile ab igni, omnia quo rerum naturae semina iacta.

27

Τὸ μὴ δῦνόν ποτε πῶς ἄν τις λάθοι;

How can one escape that which never sets?

SOURCES--Clement of Alex. Paedag. ii. 10, p. 229. Context:--For one may escape the sensible light, but the intellectual it is impossible to escape. Or, as Heraclitus says, "How can one escape that which never sets?"

28

Τὰ δὲ πάντα οἰακίζει κεραυνός.

Lightning rules all.

SOURCES-- XXVIII.--Hippolytus, Ref. haer. ix. 10. Context:--And he (Heraclitus) also says that a judgment of the world and all things in it takes place by fire, expressing it as follows, "Now lightning rules all," that is, guides it rightly, meaning by lightning, everlasting fire.

Compare Cleanthes H., Iovem 10.

29

Ἥλιος οὐχ ὑπερβήσεται μέτρα· εἰ δὲ μή, Ἐρινύες μιν δίκης ἐπίκουροι ἐξευρήσουσι.

The sun will not overstep his bounds, for if he does, the Erinyes, helpers of justice, will find him out.

SOURCES--Plutarch, de Exil. II, p. 604. Context:--Each of the planets, rolling in one sphere, as in an island, preserves its order. "For the sun," says Heraclitus, "will not overstep his bounds," etc.

Idem, de Iside 48, p. 370.

Comp. Hippolytus, Ref. haer. vi. 26.

Iamblichus, Protrept. 21, p. 132, Arcer.

Pseudo-Heraclitus, Epist. ix.

30

Ἠοῦς καὶ ἑσπέρης τέρματα ἡ ἄρκτος, καὶ ἀντίον τῆς ἄρκτου οὖρος αἰθρίου Διός.

The limits of the evening and morning are the Bear, and opposite the Bear, the bounds of bright Zeus.

SOURCES--Strabo i., 6, p. 3. Context:--And Heraclitus, better and more Homerically, naming in like manner the Bear instead of the northern circle, says, "The limits of the evening and morning are the Bear, and opposite the Bear, the bounds of bright Zeus." For the northern circle is the boundary of rising and setting, not the Bear.

31

Εἰ μὴ ἥλιος ἦν, εὐφρόνη ἂν ἦν.

If there were no sun, it would be night.

SOURCES--Plutarch, Aq. et ign. comp. 7, p. 957.

Idem, de Fortuna 3, p. 98. Context:--And just as, if there were no sun, as far as regards the other stars, we should have night, as Heraclitus says, so as far as regards the senses, if man had not mind and reason, his life would not differ from that of the beasts.

Compare Clement of Alex. Protrept. II, p. 87.

Macrobius, Somn. Scip. i. 20.

32

Νέος ἐφ' ἡμέρῃ ἥλιος.

The sun is new every day.

SOURCES--Aristotle, Meteor. ii. 2, p. 355 a 9. Context:--Concerning the sun this cannot happen, since, being nourished in the same manner, as they say, it is plain that the sun is not only, as Heraclitus says, new every day, but it is continually new.

Alexander Aphrod. in Meteor. 1.1. fol. 93 a.

Olympiodorus in Meteor. 1.1. fol. 30 a.

Plotinus, Enn. ii. 1, p. 97.

Proclus in Tim. p. 334 B.

Compare Plato, Rep. vi. p. 498 B.

Olympiodorus in Plato, Phaed. p. 201, Finckh.

33

Diogenes Laertius i. 23: δοκεῖ δὲ (scil. θαλῆς) κατά τινας πρῶτος ἀστρολογῆσαι καὶ ἡλιακὰς ἐκλείψεις καὶ τροπὰς προειπεῖν, ὥς φησιν Εὔδημος ἐν τῇ περὶ τῶν ἀστρολογουμένων ἱστορίᾳ· ὅθεν αὐτὸν καὶ Ξενοφάνης καὶ Ἡρόδοτος θαυμάζει. μαρτυρεῖ δ' αὐτῷ καὶ Ἡράκλειτος καὶ Δημόκριτος.

Diogenes Laertius i. 23. He (scil. Thales) seems, according to some, to have been the first to study astronomy and to foretell the eclipses and motions of the sun, as Eudemus relates in his account of astronomical works. And for this reason he is honored by Xenophanes and Herodotus, and both Heraclitus and Democritus bear witness to him.

34

Plutarchus, Qu. Plat. viii. 4, p. 1007: οὕτως οὖν ἀναγκαίαν πρὸς τὸν οὐρανὸν ἔχων συμπλοκὴν καὶ συναρμογὴν ὁ χρόνος οὐκ ἁπλῶς ἐστι κίνησις ἀλλ', ὥσπερ εἴρηται, κίνησις ἐν τάξει μετρον ἐχούσῃ καὶ πέρατα καὶ περιόδους. ὧν ὁ ἥλιος ἐπιστάτης ὢν καὶ σκοπός, ὁρίξειν καὶ βραβευειν καὶ ἀναδεικνύναι καὶ ἀναφαίνειν μεταβολὰς καὶ ὥρας αἳ πάντα φέρουσι, καθ' Ἡράκλειτον, οὐδὲ φαύλων οὐδὲ μικρῶν, ἀλλὰ τῶν μεγίστων καὶ κυριωτάτων τῷ ἡγεμόνι καὶ πρώτῳ θεῷ γίνεται συνεργός.

Plutarch, Qu. Plat. viii. 4, p. 1007. Thus Time, having a necessary union and connection with heaven, is not simple motion, but, so to speak, motion in an order, having measured limits and periods. Of which the sun, being overseer and guardian to limit, direct, appoint and proclaim the changes and seasons which, according to Heraclitus, produce all things, is the helper of the leader and first God, not in small or trivial things, but in the greatest and most important.

SOURCES--Compare Plutarch, de Def. orac. 12, p. 416.

M. Antoninus ix. 3.

Pseudo-Heraclitus, Epist. v.

35

Διδάσκαλος δὲ πλείστων Ἡσίοδος· τοῦτον ἐπίστανται πλείστα εἰδέναι, ὅστις ἡμέρην καὶ εὐφρόνην οὐκ ἐγίνωσκε· ἔστι γὰρ ἕν.

Hesiod is a teacher of the masses. They suppose him to have possessed the greatest knowledge, who indeed did not know day and night. For they are one.

SOURCES--Hippolytus, Ref. haer. ix. 10. Context:--Heraclitus says that neither darkness nor light, neither evil nor good, are different, but they are one and the same. He found fault, therefore, with Hesiod because he knew [not] day and night, for day and night, he says, are one, expressing it somewhat as follows: "Hesiod is a teacher of the masses," etc.

36

Ὁ θεὸς ἡμέρη εὐφρόνη, χειμὼν θέρος, πόλεμος εἰρήνη, κόρος λιμός· ἀλλοιοῦται δὲ ὅκωσπερ ὁκόταν συμμιγῇ <θυωμα> θυώμασι· ὀνομάζεται καθ' ἡδονὴν ἑκάστου.

God is day and night, winter and summer, war and peace, plenty and want. But he is changed, just as when incense is mingled with incense, but named according to the pleasure of each.

SOURCES--Hippolytus, Ref. haer. ix. 10. Context:--For that the primal (Gr. prôton, Bernays reads poiêton, created) world is itself the demiurge and creator of itself, he (Heraclitus) says as follows:" God is day and," etc.

Compare idem, Ref. haer. v. 21.

Hippocrates, peri diaitês i. 4, Littr.

37

Aristoteles, de Sensu 5, p. 443 a 21: δοκεῖ δ' ἐνίοις ἡ καπνώδης ἀναθυμίασις εἶναι ὀσμή, οὖσα κοινὴ γῆς τε καὶ ἀέρος. καὶ πάντες ἐπιφέρονται ἐπὶ τοῦτο περὶ ὀσμῆς· διὸ καὶ Ἡράκλειτος οὕτως εἴρηκεν, ὡς εἰ πάντα τὰ ὄντα καπνὸς γένοιτο, ῥῖνες ἂν διαγνοῖεν.

Aristotle, de Sensu 5, p. 443 a 21. Some think that odor consists in smoky exhalation, common to earth and air, and that for smell all things are converted into this. And it was for this reason that Heraclitus thus said that if all existing things should become smoke, perception would be by the nostrils.

38

Αἱ ψυχαὶ ὀσμῶνται καθ' ᾅδην.

Souls smell in Hades.

SOURCES--Plutarch, de Fac. in orbe lun. 28, p. 943. Context:-- Their (scil. the souls') appearance is like the sun's rays, and their spirits, which are raised aloft, as here, in the ether around the moon, are like fire, and from this they receive strength and power, as metals do by tempering. For that which is still scattered and diffuse is strengthened and becomes firm and transparent, so that it is nourished with the chance exhalation. And finely did Heraclitus say that "souls smell in Hades."

39

Τὰ ψυχρὰ θέρεται, θερμὸν ψύχεται, ὑγρὸν αὐαίνεται, καρφαλέον νοτίζεται.

Cold becomes warm, and warm, cold; wet becomes dry, and dry, wet.

SOURCES--Schol. Tzetzae, Exeget. Iliad. p. 126, Hermann. Context:--Of old, Heraclitus of Ephesus was noted for the obscurity of his sayings, "Cold becomes warm," etc.

Compare Hippocrates, peri diaitês i. 21.

Pseudo-Heraclitus, Epist. v.--Apuleius, de Mundo 21.

40

Σκίδνησι καὶ συνάγει, πρόσεισι καὶ ἄπεισι.

It disperses and gathers, it comes and goes.

SOURCES--Plutarch, de EI. 18, p. 392. Context, see frag. 41.

Compare pseudo-Heraclitus, Epist. vi.

41

Ποταμοῖσι δὶς τοῖσι αὐτοῖσι οὐκ ἂν ἐμβαίης· ἕτερα γὰρ <καὶ ἕτερα> ἐπιρρέει ὕδατα.

Into the same river you could not step twice, for other waters are flowing.

SOURCES--Plutarch, Qu. nat. 2, p. 912. Context:--For the waters of fountains and rivers are fresh and new, for, as Heraclitus says, "Into the same river," etc.

Plato, Crat. 402 A. Context:--Heraclitus is supposed to say that all things are in motion and nothing at rest; he compares them to the stream of a river, and says that you cannot go into the same river twice (Jowett's transl.).

Aristotle, Metaph. iii. 5, p. 1010 a 13. Context:--From this assumption there grew up that extreme opinion of those just now mentioned, those, namely, who professed to follow Heraclitus, such as Cratytus held, who finally thought that nothing ought to be said, but merely moved his finger. And he blamed Heraclitus because he said you could not step twice into the same river, for he himself thought you could not do so once.

Plutarch, de EI. 18, p. 392. Context:--It is not possible to step twice into the same river, according to Heraclitus, nor twice to find a perishable substance in a fixed state; but by the sharpness and quickness of change, it disperses and gathers again, or rather not again nor a second time, but at the same time it forms and is dissolved, it comes and goes (see frag 40).

Idem, de Sera num. vind. 15, p. 559.

Simplicius in Aristot. Phys. f. 17 a.

42

†Ποταμοῖσι τοῖσι αὐτοῖσι ἐμβαίνουσιν ἕτερα καὶ ἕτερα ὕδατα ἐπιρρεῖ†.

†To those entering the same river, other and still other waters flow.†

SOURCES--Arius Didymus from Eusebius, Praep. evang. xv. 20, p. 821. Context:--Concerning the soul, Cleanthes, quoting the doctrine of Zeno in comparison with the other physicists, said that Zeno affirmed the perceptive soul to be an exhalation, just as Heraclitus did. For, wishing to show that the vaporized souls are always of an intellectual nature, he compared them to a river, saying, "To those entering the same river, other and still other waters flow." And souls are exhalations from moisture. Zeno, therefore, like Heraclitus, called the soul an exhalation.

Compare Sextus Emp. Pyrrh. hyp. iii. 115.

43

Aristoteles, Eth. Eud. vii. 1, p. 1235 a 26: καὶ Ἡράκλειτος ἐπιτιμᾷ τῷ ποιήσαντι· ὡς ἔρις ἔκ τε θεῶν καὶ ἀνθρώπων ἀπόλοιτο· οὐ γὰρ ἂν εἶναι ἁρμονίαν μὴ ὄντος ὀξέος καὶ βαρέος, οὐδὲ τὰ ζῷα ἄνευ θήλεος καὶ ἄρρενος, ἐναντίων ὄντων.

Aristotle, Eth. Eud. vii. 1, p. 1235 a 26. And Heraclitus blamed the poet who said, "Would that strife were destroyed from among gods and men." For there could be no harmony without sharps and flats, nor living beings without male and female which are contraries.

SOURCES--Plutarch, de Iside 48, p. 370. Context:--For Heraclitus in plain terms calls war the father and king and lord of all (= frag. 44), and he says that Homer, when he prayed--"Discord be damned from gods and human race," forgot that he called down curses on the origin of all things, since they have their source in antipathy and war.

Chalcidius in Tim. 295.

Simplicius in Aristot. Categ. p. 104 Delta, ed. Basil.

Schol. Ven. (A) ad Il. xviii, 107.

Eustathius ad Il. xviii. 107, p. 1113, 56.

44

Πόλεμος πάντων μὲν πατήρ ἐστι πάντων δὲ βασιλεύς, καὶ τοὺς μὲν θεοὺς ἔδειξε τοὺς δὲ ἀνθρώπους, τοὺς μὲν δούλους ἐποίησε τοὺς δὲ ἐλευθέρους.

War is the father and king of all, and has produced some as gods and some as men, and has made some slaves and some free.

SOURCES--Hippolytus, Ref. haer. ix. 9. Context:--And that the father of all created things is created and uncreated, the made and the maker, we hear him (Heraclitus) saying, " War is the father and king of all," etc.

Plutarch, de Iside 48, p. 370. Context, see frag. 43.

Proclus in Tim. 54 A (comp. 24 B).

Compare Chrysippus from Philodem. P. eusebeias, vii. p. 81, Gomperz.

Lucianus, Quomodo hist. conscrib. 2; Idem, Icaromen 8.

45

Οὐ ξυνίασι ὅκως διαφερόμενον ἑωυτῷ ὁμολογέει· παλίντροπος ἁρμονίη ὅκωσπερ τόξου καὶ λύρης.

They do not understand: how that which separates unites with itself. It is a harmony of oppositions, as in the case of the bow and of the lyre.

SOURCES--Hippolytus, Ref. haer. ix. 9. Context, see frag. 1.

Plato, Symp.187 A. Context:--And one who pays the least attention will also perceive that in music there is the same reconciliation of opposites; and I suppose that this must have been the meaning of Heraclitus, though his words are not accurate; for he says that the One is united by disunion, like the harmony of the bow and the lyre (Jowett's transl.).

Idem, Soph. 242 D. Context:--Then there are Ionian, and in more recent times Sicilian muses, who have conceived the thought that to unite the two principles is safer; and they say that being is one and many, which are held together by enmity and friendship, ever parting, ever meeting (idem).

Plutarch, de Anim. procreat. 27, p. 1026. Context:--And many call this (scil. necessity) destiny. Empedocles calls it love and hatred; Heraclitus, the harmony of oppositions as of the bow and of the lyre.

Compare Synesius, de Insomn. 135 A

Parmenides v. 95, Stein.

46

Aristoteles, Eth. Nic. viii. 2, p. 1155 b 1: καὶ περὶ αὐτῶν τούτων ἀνώτερον ἐπιζητοῦσι καὶ φυσικώτερον· Εὐριπίδης μὲν φάσκων ἐρᾶν μὲν ὄμβρου γαῖαν ξηρανθεῖσαν, ἐρᾶν δὲ σεμνὸν οὐρανὸν πληρούμενον ὄμβρου πεσεῖν ἐς γαῖαν· καὶ Ἡράκλειτος τὸ ἀντίξουν συμφέρον, καὶ ἐκ τῶν διαφερόντων καλλίστην ἁρμονίαν, καὶ πάντα κατ' ἔριν γίνεσθαι.

Aristotle, Eth. Nic. viii. 2, p. 1155 b 1. In reference to these things, some seek for deeper principles and more in accordance with nature. Euripides says, "The parched earth loves the rain, and the high heaven, with moisture laden, loves earthward to fall." And Heraclitus says, "The unlike is joined together, and from differences results the most beautiful harmony, and all things take place by strife."

SOURCES--Compare Theophrastus, Metaph. 15.

Philo, Qu. in Gen. iii. 5, p. 178, Aucher.

Idem, de Agricult. 31, p. 321.

47

Ἁρμονίη ἀφανὴς φανερῆς κρείσσων.

The hidden harmony is better than the visible.

SOURCES--Hippolytus, Ref. haer. ix. 9-10. Context, see frag. 13.

Plutarch, de Anim. procreat. 27, p. 1026. Context:--Of the soul nothing is pure and unmixed nor remains apart from the rest, for, according to Heraclitus," The hidden harmony is better than the visible," in which the blending deity has hidden and sunk variations and differences.

Compare Plotinus, Enn. i. 6, p. 53.

Proclus in Cratyl. p. 107, ed. Boissonad.

48

Μὴ εἰκῆ περὶ τῶν μεγίστων συμβαλώμεθα.

Let us not draw conclusions rashly about the greatest things.

SOURCES--Diogenes Laert. ix. 73. Context:--Moreover, Heraclitus says, "Let us not draw conclusions rashly about the greatest things." And Hippocrates delivered his opinions doubtfully and moderately.

49

Χρὴ εὖ μάλα πολλῶν ἵστορας φιλοσόφους ἄνδρας εἶναι.

Philosophers must be learned in very many things.

SOURCES--Clement of Alex. Strom. v. 14, p. 733. Context:--Philosophers must be learned in very many things, according to Heraclitus. And, indeed, it is necessary that "he who wishes to be good shall often err."

50

Γναφέων ὁδὸς εὐθεῖα καὶ σκολιὴ μία ἐστὶ καὶ ἡ αὐτή.

The straight and crooked way of the woolcarders is one and the same.

SOURCES--Hippolytus, Ref. haer. ix. 10. Context:--And both straight and crooked, he (Heraclitus) says, are the same: "The way of the wool-carders is straight and crooked." The revolution of the instrument in a carder's shop (Gr. gnapheiô Bernays, grapheiô vulg.) called a screw is straight and crooked, for it moves at the same time forward and in a circle." It is one and the same," he says.

Compare Apuleius, de Mundo 21.

51

Ὄνοι σύρματ' ἂν ἕλοιντο μᾶλλον ἢ χρυσόν.

Asses would choose stubble rather than gold.

SOURCES--Aristotle, Eth. Nic. x. 5, p. 1176 a 6. Context:--The pleasures of a horse, a dog, or a man, are all different. As Heraclitus says, "Asses would choose stubble rather than gold," for to them there is more pleasure in fodder than in gold.

52

θάλασσα ὕδωρ καθαρώτατον καὶ μιαρώτατον, ἰχθύσι μὲν πότιμον καὶ σωτήριον, ἀνθρώποις δὲ ἄποτον καὶ ὀλέθριον.

Sea water is very pure and very foul, for, while to fishes it is drinkable and healthful, to men it is hurtful and unfit to drink.

SOURCES--Hippolytus, Ref. haer. ix. 10. Context:--And foul and fresh, he (Heraclitus) says, are one and the same. And drinkable and undrinkable are one and the same. "Sea water," he says; " is very pure and very foul," etc.

Compare Sextus Empir. Pyrrh. hyp. i. 55.

53

Columella, de Re Rustica viii. 4: siccus etiam pulvis et cinis, ubicunque corhortem porticus vel tectum protegit, iuxta parietes reponendus est, ut sit quo aves se perfundant: nam his rebus plumam pinnasque emendant, si modo credimus Ephesio Heraclito qui ait: sues coeno, cohortales aves pulvere (vel cinere) lavari.

Columella, de Re Rustica viii. 4. Dry dust and ashes must be placed near the wall where the roof or eaves shelter the court, in order that there may be a place where the birds may sprinkle themselves, for with these things they improve their wings and feathers, if we may believe Heraclitus, the Ephesian, who says, "Hogs wash themselves in mud and doves in dust."

SOURCES--Compare Galenus, Protrept. 13, p. 5, ed. Bas.

54

Βορβόρῳ χαίρειν.

They revel in dirt.

SOURCES--Athenaeus v. p. 178 F. Context:--For it would be unbecoming, says Aristotle, to go to a banquet covered with sweat and dust. For a well-bred man should not be squalid nor slovenly nor delight in dirt, as Heraclitus says.

Clement of Alex. Protrept. 10, p. 75.

Idem, Strom. i. 1, p. 317; ii. 15, p. 465.

Compare Sextus Empir. Pyrrh. hyp. i. 55.

Plotinus, Enn. i. 6, p. 55.

Vincentius Bellovac. Spec. mor. iii. 9, 3.

55

Πᾶν ἑπρετὸν πληγῇ νέμεται.

Every animal is driven by blows.

SOURCES--Aristotle, de Mundo 6, p. 401 a 8 (=Apuleius, de Mundo 36; Stobaeus, Ecl. i. 2, p. 86). Context:--Both wild and domestic animals, and those living upon land or in air or water, are born, live and die in conformity with the laws of God. "For every animal," as Heraclitus says, "is driven by blows" (plêgê Stobaeus cod. A, Bergklus et al.; vulg. tên gên nemetai, every animal feeds upon the earth).

56

Παλίντροπος ἁρμονίη κόσμου ὅκωσπερ λύρης καὶ τόξου.

The harmony of the world is a harmony of oppositions, as in the case of the bow and of the lyre.

SOURCES--Plutarch, De Tranquill. 15, p. 473. Context:--For the harmony of the world is a harmony of oppositions (Gr. palintonos harmoniê, see Crit. Note 21), as in the case of the bow and of the lyre. And in human things there is nothing that is pure and unmixed. But just as in music, some notes are flat and some sharp, etc.

Idem, de Iside 45, p. 369. Context:--"For the harmony of the world is a harmony of opposition, as in the case of the bow and of the lyre," according to Heraclitus; and according to Euripides, neither good nor bad may be found apart, but are mingled together for the sake of greater beauty.

Porphyrius, de Antro. nymph. 29.

Simplicius in Phys. fol. 11 a.

Compare Philo, Qu. in Gen. iii. 5, p. 178, Aucher.

57

Ἀγαθὸν καὶ κακὸν ταὐτόν.

Good and evil are the same.

SOURCES--Hippolylus, Ref. haer. ix. 10. Context, see frag. 58.

Simplicius in Phys. fol. 18 a. Context:--All things are with others identical, and the saying of Heraclitus is true that the good and the evil are the same.

Idem on Phys. fol. 11 a.

Aristotle, Top. viii. 5, p. 159 b 30.

Idem, Phys. i. 2, p. 185 b 20.

58

Hippolytus, Ref. haer. ix. 10: καὶ ἀγαθὸν καὶ κακόν (scil. ἕν ἐστι)· οἱ γοῦν ἰατροί, φησὶν ὁ Ἡράκλειτος, τέμνοντες καίοντες πάντη βασανίζοντες κακῶς τοὺς ἀρρωστοῦντας ἐπαιτιῶνται μηδέν' ἄξιον μισθὸν λαμβάνειν παρὰ τῶν ἀρρωστούντων, ταῦτα ἐργαζόμενοι τὰ ἀγαθὰ καὶ †τὰς νόσους.†

Hippolytus, Ref. haer. ix. 10. And good and evil (scil. are one). The physicians, therefore, says Heraclitus, cutting, cauterizing, and in every way torturing the sick, complain that the patients do not pay them fitting reward for thus effecting these benefits-- †and sufferings†.

SOURCES--Compare Xenophon, Mem. i. 2, 54.

Plato, Gorg. 521 E; Polit. 293 B.

Simplicius in Epictetus 13, p. 83 D and 27, p. 178 A, ed. Heins.

59

Συνάψειας οὖλα καὶ οὐχὶ οὖλα, συμφερόμενον διαφερόμενον, συνᾷδον διᾷδον· ἐκ πάντων ἓν καὶ ἐξ ἑνὸς πάντα.

Unite whole and part, agreement and disagreement, accordant and discordant; from all comes one, and from one all.

SOURCES-- Aristotle, de Mundo 5, p. 396 b 12 (=Apulelus, de Mundo 20; Stobaeus, Ecl. i. 34, p. 690). Context:--And again art, imitator of nature, appears to do the same. For in painting, it is by the mixing of colors, as white and black or yellow and red, that representations are made corresponding with the natural types. In music also, from the union of sharps and flats comes a final harmony, and in grammar, the whole art depends on the blending of mutes and vocables. And it was the same thing which the obscure Heraclitus meant when he said, "Unite whole and part," etc.

Compare Apuleius, de Mundo 21.

Hippocrates peri trophês 40; peri diaitês i.

60

Δίκης οὔνομα οὐκ ἂν ᾔδεσαν, εἰ ταῦτα μὴ ἦν.

They would not know the name of justice, were it not for these things.

SCOURCES-- Clement of Alex. Strom. iv. 3, p. 568. Context:--For the Scripture says, the law is not made for the just man. And Heraclitus well says, "They would not know the name of justice, were it not for these things."

Compare pseudo-Heraclitus, Epist. vii.

61

Schol. B. in Iliad iv. 4, p. 120 :Bekk. ἀπρεπές φασιν, εἰ τέρπει τοὺς θεοὺς πολέμων θέα. ἀλλ' οὐκ ἀπρεπές· τὰ γὰρ γενναῖα ἔργα τέρπει. ἄλλως τε πόλεμοι καὶ μάχαι ἡμῖν μὲν δεινὰ δοκεῖ, τῷ δὲ θεῷ οὐδὲ ταῦτα δεινά. συντελεῖ γὰρ ἅπαντα ὁ θεὸς πρὸς ἁρμονίαν τῶν ὅλων, οἰκονομῶν τὰ συμφέροντα, ὅπερ καὶ Ἡράκλειτος λέγει, ὡς τῷ μὲν θεῷ καλὰ πάντα καὶ ἀγαθὰ καὶ δίκαια, ἄνθρωποι δὲ ἃ μὲν ἄδικα ὑπειλήφασιν, ἃ δὲ δίκαια.

Schol. B. in Iliad iv. 4, p. 120 :Bekk. They say that it is unfitting that the sight of wars should please the gods. But it is not so. For noble works delight them, and while wars and battles seem to us terrible, to God they do not seem so. For God in his dispensation of all events, perfects them into a harmony of the whole, just as, indeed, Heraclitus says that to God all things are beautiful and good and right, though men suppose that some are right and others wrong.

SOURCES-- Compare Hippocrates, peri diaitês i. 11.

62

Εἰδέναι χρὴ τὸν πόλεμον ἐόντα ξυνόν, καὶ δίκην ἔριν· καὶ γινόμενα πάντα κατ' ἔριν καὶ †χρεώμενα†.

We must know that war is universal and strife right, and that by strife all things arise and † are used †

SCOURCES-- Origen, cont. Celsus vi. 42, p. 312 (Celsus speaking). Context:--There was an obscure saying of the ancients that war was divine, Heraclitus writing thus, "We must know that war," etc.

Compare Plutarch, de Sol. animal. 7, p. 964.

Diogenes Laert. ix. 8.

63

Ἔστι γὰρ εἱμαρμένα πάντως ...

For it is wholly destined ...

Sources-- Stobaeus Ecl. i. 5, p. 178. Context:--Heraclitus declares that destiny is the all-pervading law. And this is the etherial body, the seed of the origin of all things, and the measure of the appointed course. All things are by fate, and this is the same as necessity. Thus he writes, "For it is wholly destined" (The rest is wanting).

64

Θάνατός ἐστι ὁκόσα ἐγερθέντες ὁρέομεν, ὁκόσα δὲ εὕδοντες ὕπνος.

Death is what we see waking. What we see in sleep is a dream.

SOURCES--Clement of Alex. Strom. iii. 3, p. 520. Context:--And does not Heraclitus call death birth, similarly with Pythagoras and with Socrates in the Gorgias, when he says, "Death is what we see waking. What we see in sleep is a dream"?

Compare idem v. 14, p. 712. Philo, de Ioseph. 22, p. 59.

65

Ἓν τὸ σοφὸν μοῦνον· λέγεσθαι οὐκ ἐθέλει καὶ ἐθέλει Ζηνὸς οὔνομα.

There is only one supreme Wisdom. It wills and wills not to be called by the name of Zeus.

SOURCES-- Clement of Alex. Strom. v. 14, p. 718 (Euseb. P. E. xiii. 13, p. 681). Context:--I know that Plato also bears witness to Heraclitus' writing, "There is only one supreme Wisdom. It wills and wills not to be called by the name of Zeus." And again, "Law is to obey the will of one " (= frag. 110).

66

Τοῦ βιοῦ οὔνομα βίος, ἔργον δὲ θάνατος.

The name of the bow is life, but its work is death.

SOURCES-- Schol. in Iliad i. 49, fr. Cramer, A. P. iii. p. 122. Context:--For it seems that by the ancients the bow and life were synonymously called bios. So Heraclitus, the obscure, said, "The name of the bow is life, but its work is death."

Etym. magn. under word bios.

Tzetze's Exeg. in Iliad, p. 101 Herm.

Eustathius in Iliad i. 49, p. 41.

Compare Hippocrates, peri trophês 21.

67

Ἀθάνατοι θνητοί, θνητοὶ ἀθάνατοι, ζῶντες τὸν ἐκείνων θάνατον τὸν δὲ ἐκείνων βίον τεθνεῶτες.

Immortals are mortal, mortals immortal, living in their death and dying in their life.

SOURCES-- Hippolytus, Ref. haer. ix. 10. Context:--And confessedly he (Heraclitus) asserts that the immortal is mortal and the mortal immortal, in such words as these, "Immortals are mortal," etc.

Numenius from Porphyr. de Antro nymph. 10. Context, see frag. 72.

Philo, Leg. alleg. i. 33, p. 65.

Idem, Qu. in Gen. iv. 152, p. 360 Aucher.

Maximus Tyr. x. 4, p. 107. Idem, xli. 4, p. 489.

Clement of Alex. Paed. iii. 1, p. 251.

Hierocles in Aur. carm. 24.

Heraclitus, Alleg. Hom. 24, p. 51 Mehler.

Compare Lucianus, Vit. auct. 14.

Dio Cassius frr. i--xxxv. c. 30, t. i. p. 40 Dind.

Hermes from Stob. Ecl. i. 39, p. 768. Idem, Poemand. 12, p. 100.

68

Ψυχῇσι γὰρ θάνατος ὕδωρ γενέσθαι, ὕδατι δὲ θάνατος γῆν γενέσθαι· ἐκ γῆς δὲ ὕδωρ γίνεται, ἐξ ὕδατος δὲ ψυχή.

To souls it is death to become water, and to water it is death to become earth, but from earth comes water, and from water, soul.

SOURCES-- Clement of Alex. Strom. vi. 2, p. 746. Context:--(On plagiarisms) And Orpheus having written, "Water is death to the soul and soul the change from water; from water is earth and from earth again water, and from this the soul welling up through the whole ether"; Heraclitus, combining these expressions, writes as follows: " To souls it is death," etc.

Hippolytus, Ref. haer. v. 16. Context:--And not only do the poets say this, but already also the wisest of the Greeks, of whom Heraclitus was one, who said, "For the soul it is death to become water."